The propaganda trick that sparked a movement

Thanks to redistricting, all 15 seats on the Texas State Board of Education are up for re-election in the upcoming midterms. Thirty-three candidates are vying for the seats, and as you'd guess, critical race theory comes up frequently in their campaigns.

Critical race theory is not, and never was, taught in Texas public schools. But that hasn't seemed to matter.

According to the Texas Tribune, "Two Republican incumbents on the state board lost their primaries to candidates promising to get critical race theory out of classrooms." In 2021 the state passed a law banning teachers from causing their students "discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress" based on their race or sex.

How critical race theory became a household word and policy driver is a story of the power of information and those who manipulate it. If you're like me and have been astonished by this particular example, read on.

Insights from the source

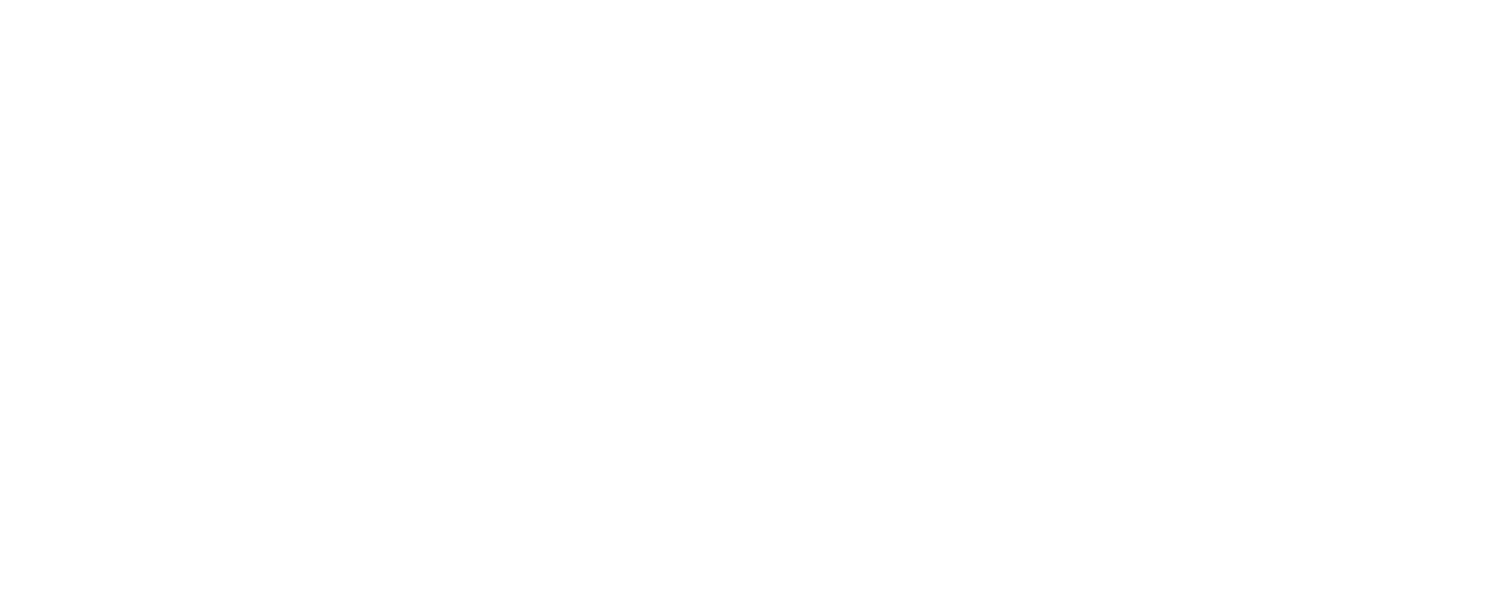

By chance, I met one of the scholars who conceptualized critical race theory, Kimberlé Crenshaw. She was speaking at The Atlantic Festival in August about how the theory hit the public agenda in 2020 and began to drive policy, almost overnight.

It was an honor to meet her and hear her talk about critical race theory and the dog whistle it's become, first-hand. Since people are either confused – and rightly so, since CRT has been discussed largely in legal circles before now – or have chosen their sides on the topic without taking the time to find out what it actually is, it was good to hear from the source.

Crenshaw expressed frustration that the "whys" behind the debate remain so elusive, and I agree. Even though there have been many insightful articles, including those in The New Yorker, Reuters, and the Brookings Institute blog that I link to in this piece, most people see a fraction of what's published on any given topic. They may not read too far beyond the headline, or they may distrust or lack access to the outlets doing the investigative work.

Unfortunately, while we've been trying to sort it out politicians and pundits grasped the CRT term and leveraged it as a tool that, as Crenshaw mentioned, has already done damage to our democratic processes.

Critical race theory, defined

During her panel, Crenshaw summed up CRT as "a study of how law contributes to inequality." It says that bias and discrimination against Black and African-American folks is embedded in our legal system and institutions in the U.S.

That's not to say that other races and ethnicities aren't affected by bias and discrimination. But the attorneys who shaped CRT were focused in particular on the lingering effects of slavery on Black people and the legal system in the U.S. Crenshaw explains herself in this Q&A in the Washington Post from last January.

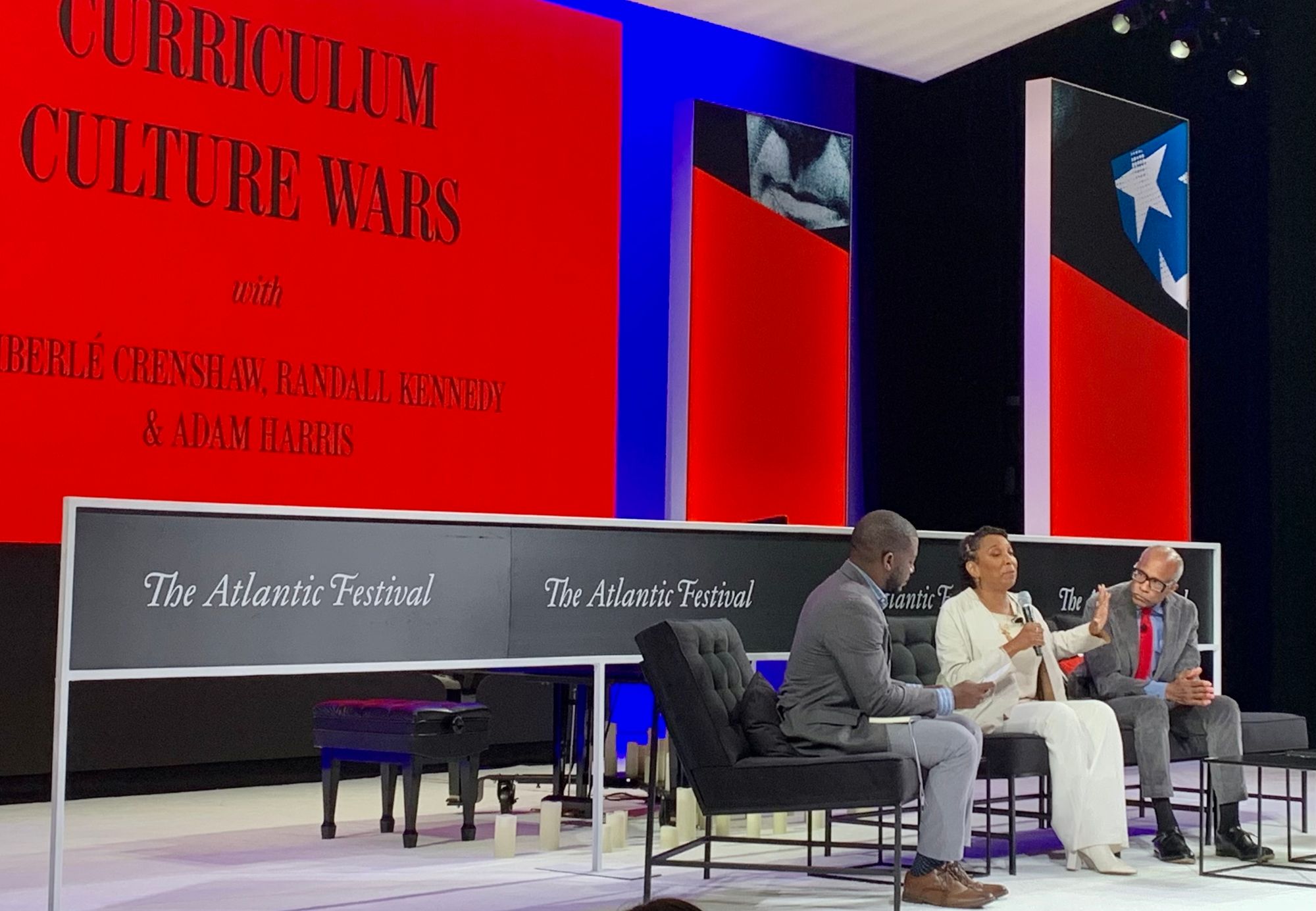

You can see the effects of systemic racism in legal documents like housing deeds. Many deeds for older homes contain covenants that say that the home may not be sold or gifted to Black people. Here's an excerpt from a deed for a home in Chevy Chase, a suburb of Washington, DC, that surfaced during some racial justice work we did at my church:

Note the exception, albeit limited, for domestic servants. In Chevy Chase, racial covenants like these were enforceable until 1948 and weren't outlawed until 1968. In other words, during my lifetime and maybe yours.

Redlining has also been exposed in mortgage lending, where banks either refused to lend to minorities or women or charged them higher interest rates than White borrowers. To understand racial bias in our court systems, one need only read the gripping book Just Mercy, about Americans who spent decades on death row for crimes they didn't commit – and the attorney working to right this wrong.

These are truths in America. Advocates are working to make these systems more equitable, but there's a long way to go.

Why the CRT debate needs further examination

I can't imagine that, when shown a housing deed like the one above, people would deny its existence. I think most would agree that it's unfair. So what's at issue here?

This Brooking's Institution piece does a good job explaining that the CRT debate immediately became about a theory that vilifies people – White people – rather than one that shines a light on systems that need fixing, as CRT is designed to do.

Which makes sense given the well-documented motives of those who thrust CRT onto the public stage and amplified it to the point where it's now a) something that everyone is talking about and b) driving policy proposals – in 42 states to date.

Yes, you read that correctly.

How on earth is that possible?

It started with an opinion

On September 2, 2020, with the world reeling from the pandemic and high-profile incidents of racial injustice, a conservative activist named Christopher Rufo appeared on Tucker Carlson Tonight and did a three-minute monologue that centered on critical race theory. He talked about "diversity training" that was happening at Federal agencies and said it was informed by critical race theory, which, he said, was fast becoming "the default ideology of the federal bureaucracy and is now being weaponized against the American people."

A good organizational development training of this ilk would open our eyes to the bias that occurs naturally in our brains and can prompt us to treat people who are different from us, differently or even in a discriminatory fashion – usually without even realizing it. It would encourage us to notice and pause so you can do better next time.

If these trainings are pretty common, why the fuss? Let's look at how Rufo got to this point.

He's a journalist and to be fair, wasn't alone in his objections – people had been sharing with him the content of trainings they'd participated in, ostensibly because they objected to the content as well, and he wrote pieces in conservative publications that racked up millions of views. Read more about Rufo's rise in this New Yorker piece.

What's important is that Rufo extracted critical race theory from sources in the trainers' footnotes and saw in it a perfect term to label the culture wars, then used it to gin up controversy across the board.

Rufo disclosed his intent to the New Yorker reporter, Ben Wallace-Wells, saying he was looking for a lever and found it in a term that was new to most, conveyed a sense of urgency and included words that would be sure to grab folks' attention.

That it did. Later that month, President Trump banned these workshops across the Federal government.

A "data void" at work

Those who used critical race theory as a political lever in 2020 were leveraging a propaganda technique called a data void.

After Rufo put CRT out there, conservative voices like Dan Shapiro and Carlson himself ran with it, saying the theory and trainings were racist themselves -- meant to attack White people and make them feel bad. Since no one knew what CRT actually was, pundits were free to explain it however they liked. And they talked about it incessantly – on Fox alone, CRT was mentioned around 1300 times in less than four months after Rufo's appearance.

Here's a perfect example of the data void at work. On November 3, 2021, Tucker Carlson said these three sentences in succession, when conversing with Brit Hume:

Sentence 2: "They're teaching that some races are morally superior to others; that some are inherently sinful and some are inherently saintly, and it's immoral to teach that, because it's wrong." Defines it himself and adds judgement language, with a religious bent

Sentence 3: "That would be my view, and I think most voters' view." Takes it to the political arena

You can cover a lot of ground in just three sentences, can't you?

If you want to watch the segment above, it's included in this Yahoo Enterainment piece.

From commentary to policy

Meanwhile, California parents had been reporting to Rufo that anti-racist themes were showing up in their kids' schools. This proved the perfect opportunity for Rufo and other pundits to take the CRT debate to another taxpayer-funded arena – public education.

You know how long it took for CRT to migrate from Rufo's initial Fox appearance in September 2020 to state-level education policy?

Four months. By the following January, it had been included in policy proposals in 13 states.

For change to happen that fast a few factors need to be present:

- Triggering emotion and identity – The politically motivated saw CRT as a perfect rallying cry for parents: They're teaching that White people are bad, and what's more you're not being consulted about it! You need to have a voice! This made parents feel like they weren't being good stewards of their kids' educations, which challenges their identities as caregivers. Calling CRT racist itself was icing on the cake (and so ironic for CRT scholars, I'm sure).

- Repetition – Messages were shared endlessly and across multiple channels. Imagine reading or hearing about the evils of CRT multiple times a day. If you happen to share one of the messages, algorithms boost it and show you more. This is how a propaganda campaign takes off.

A career-defining opportunity

In the anti-CRT movement that emerged in 2020 and 2021, parents mobilized, created Facebook groups and nonprofits. That November they helped vote candidates like Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin, who ran on anti-CRT/parent voice as a platform, into office.

Youngkin then made good on his campaign promise. Hours after his swearing in he issued an executive order to end "the use of divisive concepts, including Critical Race Theory," in K-12 public education.

He compelled Virginia's Superintendent of Public Instruction to review policies, training and recent curricular amendments statewide and remove anything that promoted inherently divisive concepts. Interestingly, the order also acknowledges the "horrors of slavery and segregation" and mistreatment of Native communities – and promotes the teaching of fact-based history.

What's important is that Virginia's EdEquityVA program, which establishes the state's priorities and practices for helping ensure lessons accommodate ALL Virginia students, is now gone.

Education has always been about equity – it's one space where entities actively work to deliver on this aspiration, rather than just batting the term around. Unfortunately, Virginia is now doing so without a roadmap.

CRT debates erupt in violence

Two January 2022 episodes of The Daily podcast called The School Board Wars tell the story of Bucks County, PA, where, fueled by debates over masks and CRT, school board meetings were exploding in shouting and personal attacks, even death threats against school board members.

Try Googling "how many school board members resigned this year?" You'll see pages and pages of local stories about members who, tired of the drama and often feeling unsafe, stepped down – often mid-term. An NPR piece from August 2021 led with a school board member in New Mexico who, after repeated attacks, had thoughts of suicide before they quit.

Sadly, poor adult behavior can trickle down – reports of racist bullying and harassment among students ticked up as well in 2021.

What's to be done?

In my view, the war we need to pay more attention to in the U.S. is one of information – its ability to be weaponized and in the blink of an eye, drive policy change, alter careers and sever relationships. The vectors are digital platforms and to an extent, reporting that amplifies without correcting falsehoods or getting at the "whys" behind the meteoric rise and politicization of obscure concepts.

I don't like policy being driven by propaganda, especially when we're dealing with an educational achievement gap that widened during the pandemic as families struggled with remote learning, illness and job loss.

As depressing as this all is, though, I promise that all is not lost. I think that if most people participated in a reasoned discussion about how certain groups have been discriminated against over time, with examples, they'd agree those examples are unfair. And schools are resilient places; I'm sure that many are figuring out how to stay focused on educational equity even amid the policy hurdles and drama; for this we owe them our endless thanks.

People are also getting fed up with the erosion of fact-based information and the trash and attack culture that's emerged. Over 500 organizations in the ListenFirst coalition, where Truth in Common is a member, are working daily to bridge our divides. In a matter of days, we'll have a chance to vote some of the propagandists out of office.

Voting isn't all we can do, though. Each one of us can push back.

Stay tuned for part 2, which will help you do just that.