Voters say no to corruption in Guatemala

This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.

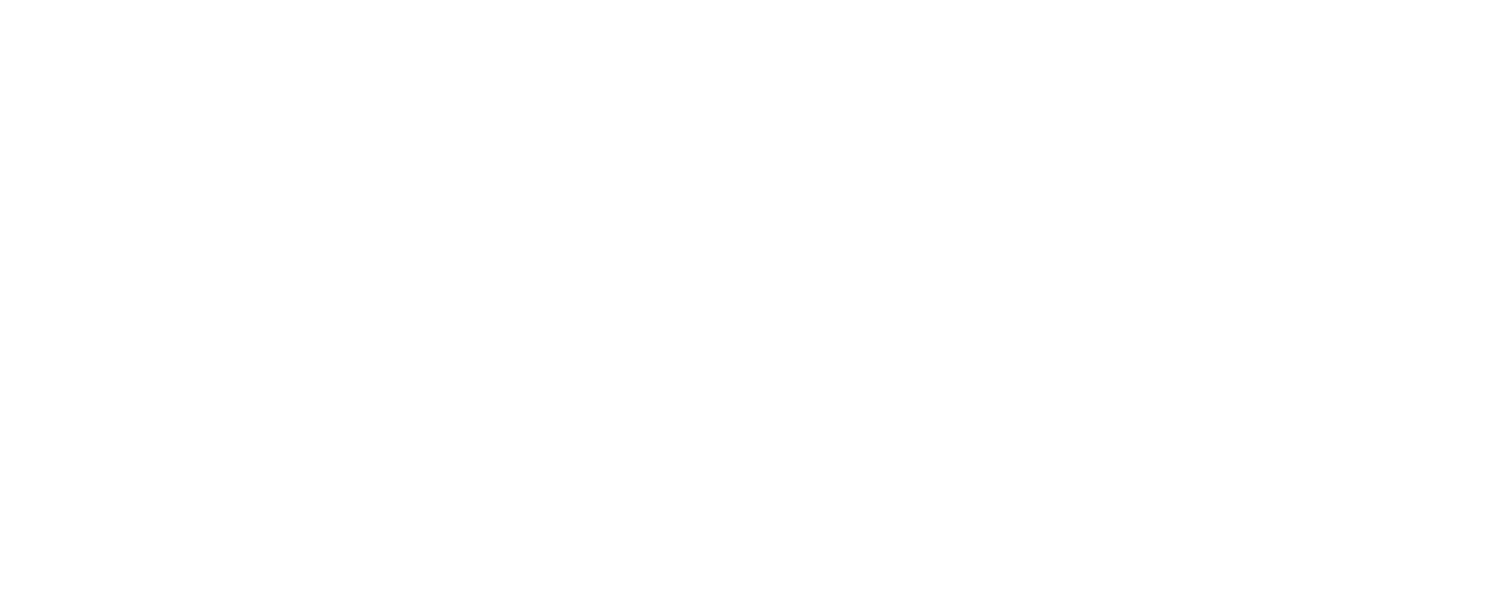

On August 20, Guatemalans voted an upset candidate into office. Bernardo Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party went from polling in the single digits to second place in the June 25 general election, then beat three-time candidate Sandra Torres by a landslide in the August run-off.

The win sent Guatemalans into the street to celebrate, shocked the political establishment and sparked cries of fraud that ring familiar in a growing number of democracies.

Election volunteer Gabriela García Quinn played a part in the evolving situation as she supported Arévalo and other anti-corruption candidates from her home town of Guatemala City. She had to counter disinformation and set aside fears of political violence as she worked for change, in a story that brings to mind the illegal and strong-arm tactics being used to discredit elections here in the U.S.

From citizen fact-checkers to collaborative journalism: Debunking falsehoods around Guatemala's election

In the August run-off that determined Guatemala's president, Bernardo Arévalo won a major victory, earning 61 percent of the vote against three-time candidate and former first lady Sandra Torres.

The initial election in June was a different story. In a fractured field of over 20 candidates, Arévalo won just 11.8 percent of the vote and Torres, 16 percent. The remaining ballots were either blank, errant or abstentions – an apparent rebuttal to the blatant barring of viable candidates by the election oversight body, the Tribuno Supremo Electoral (or Supreme Electoral Tribunal), and the courts. Since neither candidate won 50 percent of the vote, a run-off was scheduled for August 20.

What it looked like on the ground

Gabriela García Quinn grew up in Guatemala City, lived in the United States for 13 years then moved back with her husband and daughter in 2006 to be closer to family and enjoy a more reasonable cost of living. She lives in an established, walkable neighborhood, has a lhasa apso named Luna and works in international development.

García Quinn connected with Movimiento Semilla (Seed Movement), when it was just taking shape as a party, having emerged from the 2015 corruption scandal that led then-President Otto Pérez Molina to resign. She appreciated Semilla's focus on equal opportunity and its grassroots approach – party reps walked the streets and talked with people.

"Guatemala is a small country; those in your circle become friends and family." She'd always voted, but in Semilla saw the potential to vote for people she believed in and identified with. "I got into sharing my passion for politics with folks with like-minded ideas."

She followed Semilla on social media, got involved and became a registered member. For this year's election, she decided to work the polls. "I loved it," she said.

A sleeper victory

Guatemala is largely conservative and mostly Catholic, with close to 30 parties vying for power. Though Semilla is categorized as a social democratic party like Torres's Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (National Unity of Hope), initial opposition to the party was swift, with its members labelled as Communists and far-left extremists. Rumors spread that Semilla was pro-abortion. "I thought, where is this coming from?" García Quinn said. "Semilla has never spoken about that as an issue in their government plan."

Guatemala also has a long history of corruption, fueled in part by 36 years of civil war. A UN-backed Commission Against Impunity known as the CICIG was established in 2007 and brought forward 120 cases in 12 years, including the investigation of President Molina and his deputies. CICIG was disbanded in 2019 by President Jimmy Morales after he too came under investigation, which led to an uptick in anti-democratic activities since.

Arévalo's legacy is strong – his father was the first democratically elected president in Guatemala and a legend in the country's fight against corruption. But in May Arévalo's poll numbers were anemic. No one expected him to do well in the general election.

The government's disqualification of candidates, though, aggravated voters, especially younger ones, and pushed votes Arévalo's way, according to García Quinn. When people awoke on June 26 to see he'd made the run-off, "Guatemala was in shock."

A swift response

When her run-off opponent became clear, Torres – historically a left-leaning advocate for the poor – began claiming that Arévalo would legalize abortion, gay marriage and tell families they can choose their kids' genders, García Quinn said. Extremist faith leaders said an Arévalo presidency meant the devil is coming.

The establishment legal machine kicked in as well.

According to Manuel Menéndez-Sánchez, a PhD candidate in political science at Harvard University, the months between election and run-off saw a series of actions by a regime determined to block the emerging leader. "Until the runoff happened, no one could say with certainty that it would happen," he said.

On the Lawfare podcast episode "An Earthshattering Election in Guatemala," Menéndez-Sánchez described a string of anti-democratic activities after the June 25 vote. His comments and other reporting suggest a timeline that looks like this:

- June 30 – The Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE) party and allies called for a recount, claiming irregularities.

- July 1 – The Constitutional Court ordered an audit; Arévalo and Semilla's wins were upheld.

- July 12 – The public prosecutor's office claimed signatures were falsified by Semilla party members and accused the party of money laundering. Judge Freddy Orellana granted a request to de-certify Semilla, which caused an uproar and was condemned by the U.S. and other countries.

- July 13 – The Tribuno Supremo Electoral (TSE) certified the June 25 vote count. The Constitutional Court granted an injunction against Orellana and Attorney General María Consuelo Porras on the grounds that trying to de-list a party in an active election is unconstitutional.

- July 13-21 – Undeterred, Orellana ordered raids on TSE and Semilla offices and tried to arrest the head of TSE and members of Semilla.

- July 23 – The Constitutional Court reinforced its earlier injunction.

- Throughout, party members feared arrest and left the country, online trolling was rampant and at least one assassination plot prompted Arévalo and his running mate, Karin Herrera, to reduce public appearances.

As citizens expressed their outrage at these activities, the promise of ending decades of corruption in Guatemala seemed remote.

Correcting the record

García Quinn had grown accustomed to challenging falsehoods about Semilla, but now found herself debunking disinformation about the election overall.

Sixty percent of Guatemala's 17 million people have internet access, according to an International Republican Institute report. Facebook, YouTube and TikTok are most popular among social media users; only Facebook and Instagram were approved by TSE to run labelled political ads.

According to García Quinn, Movimiento Semilla used TikTok, Facebook Live and quality journalism as tools for countering the spread of falsehoods about the election and its candidates. In this Facebook live video from the Constitutional Court, party representatives object to Orellana's ongoing, unconstitutional attacks.

García Quinn also finds it efficient to curate and follow quality news sources on Twitter. By engaging respectfully and having facts on hand, she became a trusted resource as well. With credibility from her poll work and experience, she was frequently tapped to validate content people saw. "A friend called me an influencer for quality information," she said.

"We're living in a surreal world in my country," she said. "I want to put out for my friends and family the sources I think are factual, then they decide. I can't sit down and do nothing."

Media outlets step up

Guatemala ranks 127 on Reporters Without Borders' Global Press Freedom Index. Just before the June election, top journalist José Rubén Zamora was convicted of money laundering charges and sentenced to six years in prison in a move many view as retaliation for his work to expose government corruption.

Yet independent journalists stepped up before and after the election, launching a joint response to disinformation and anti-democratic activity called La Linterna, or The Lantern. In an effort they dubbed "collaborative journalism for democracy," five Guatemalan outlets joined forces to fact-check campaign messages, do investigative journalism around the election and verify candidates' debate statements in real-time. Partners include ConCriterio , elPeriódico , No-Ficción and Ojoconmipisto, with coordination by Ocote.

In this piece, La Linterna reporters debunked a fake announcement of cabinet members that was circulated on Semilla party letterhead just days before the run-off. (It's in Spanish but you can choose "translate this page" via an icon in the search bar at the top.)

La nueva primavera

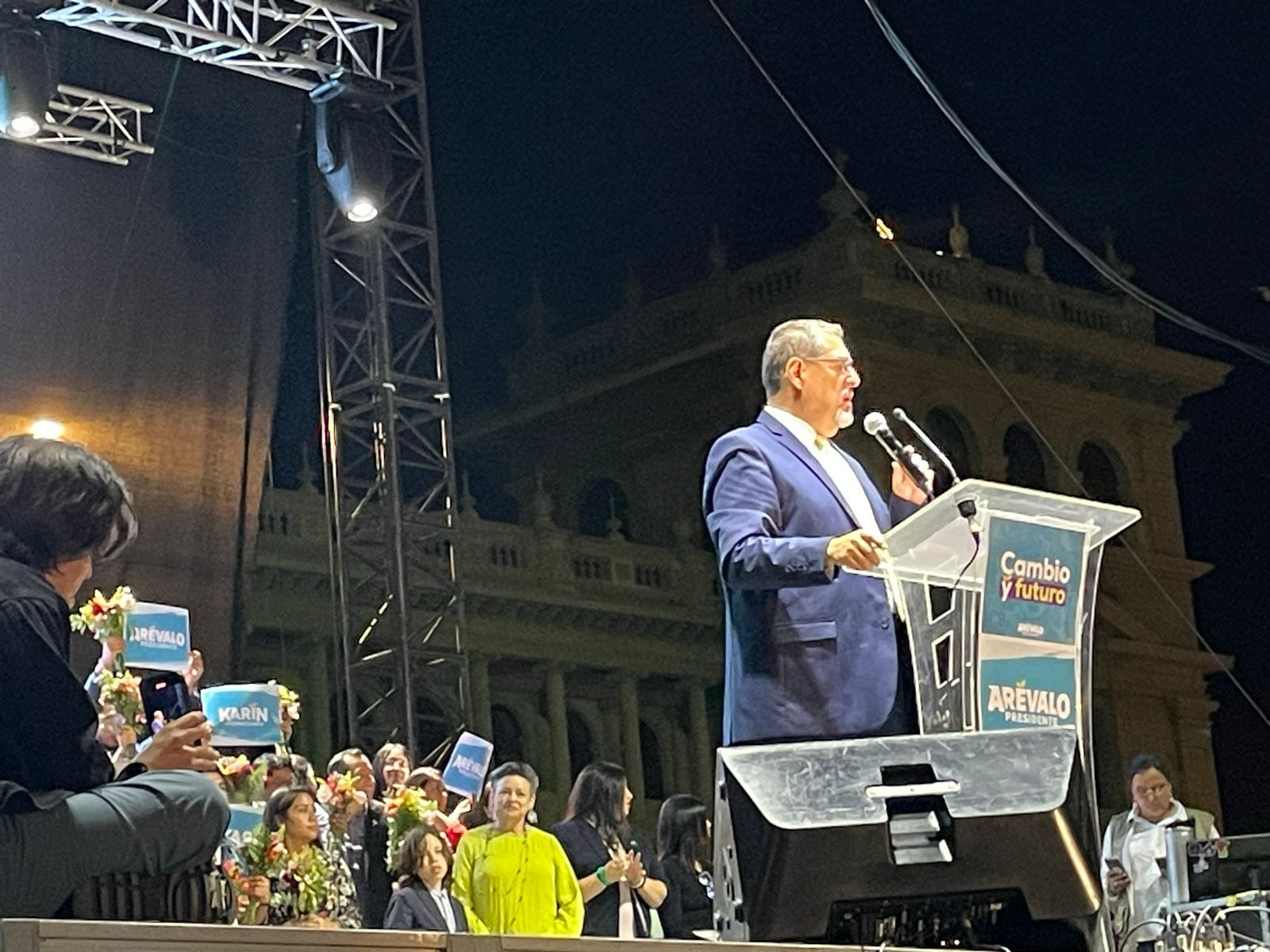

Arévalo and Herrera weren't the only Semilla candidates to win this year. In Guatemala's Congreso de República (Congress of the Republic), the party won 23 out of 160 seats, eclipsing last election's performance by a factor of four in a wave that's been called la nueva primavera, or the new spring, a reminder of the original Guatemalan spring in 1944 when Arévalo's father took office.

The president-elect, however, is by no means out of the woods.

Claims of fraud persist and new disinformation efforts say that since he was born in Uruguay, Arévalo is ineligible to serve.

Sound familiar?

Given the threat of continued attacks and spooked by the assassination of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio in Ecuador on August 9, the Guatemalan government has finally tightened security around Arévalo, Herrera and their families.

On August 29 the U.S. Department of State issued a statement supporting the president-elect and denouncing the rash of anti-democratic activity. This week, the Organization of American States denounced the public prosecutor's office for "questioning the electoral process and intimidating electoral authorities, electoral personnel and the thousands of people who, with great civic commitment, carried out two days of peaceful and transparent voting." Current president Alejandro Giammattei has invited OAS chief Luis Almagro to remain in Guatemala as an observer until the January inauguration.

And as Daniel Valencia wrote in No Ficción, despite the Semilla victories Arévalo will face an opposition majority in Congress and perhaps the hostility of neighboring Latin American leaders as well.

A lesson for other nations

The election results are a win, albeit a cautious one, for integrity in government and the Guatemalans who've fought hard to achieve it. Neither candidates nor supporters have lost sight of the risks or the rewards as Arévalo and a notable number of women candidates-elect move closer to taking their seats in January.

You may not spend a lot of time thinking about Guatemala. But we'd be wise to recognize the parallels between the last few months there and the last few years here in the United States. And as 13 U.S. presidential centers noted in an unprecedented letter on September 7, we should note and support democratic movements around the world.

The centers also urged us to clean up our political discourse here. The world is watching, and democracy is no guarantee. It can, though, be protected through the dedicated, grassroots responses of citizens, journalists, civil society and supporters who call out illegal activity and stand up for the truth.

Deanna Troust is founder and president of Truth in Common and 3 Stories Communications. Visit www.truthincommon.org or follow Deanna on LinkedIn, Twitter, Threads or Instagram.